Potential Energy: Making Random Encounters Consistently Awesome

First, a reminder that I have joined Shawn Merwin, co-hosting the Down with D&D Podcast! Last week we discussed New Players, and how best to bring them into the game. This week we will discuss Exploration. Many of the concepts tie into the concept of potential energy.

Let’s take a further look at designing adventures using the design principle of potential energy: adventure scenes can be written to encourage players to engage with scene elements and create their own cool moments.

Aside: Leon Barillaro was the awesome editor on a recent project you should check out, Scientific Secrets of Avernus (it takes real-world creatures and turns them into hellish D&D creatures – I contributed the Flesh-Eating Splendor Swarm, and I think it is wonderfully horrid).

Leon Barillaro wrote a blog post about designing combats, and it reminded me that potential energy solves many common complaints, such as:

- My players destroy any monsters I put before them!

- Combat feels like a slog. Sacks of hit points slowly dwindling.

- Half the table looked bored.

- The encounter was a waste of time.

When we use the design principle of potential energy, our encounters have engagement beyond combat challenge, or beyond the basic premise of the encounter (disarm the trap, talk to the NPC, etc).

It won’t matter if the combat is too easy, because the players will engage with the elements in the scene and have a sense of purpose. It won’t matter if the monsters have too many hit points, because killing them isn’t the most important goal or isn’t the only source of fun in the scene. It won’t matter if there isn’t a spectacular roleplaying moment between a PC and the NPC, because other scene elements or the overall stakes make it enjoyable and interesting for everyone.

Random Encounters

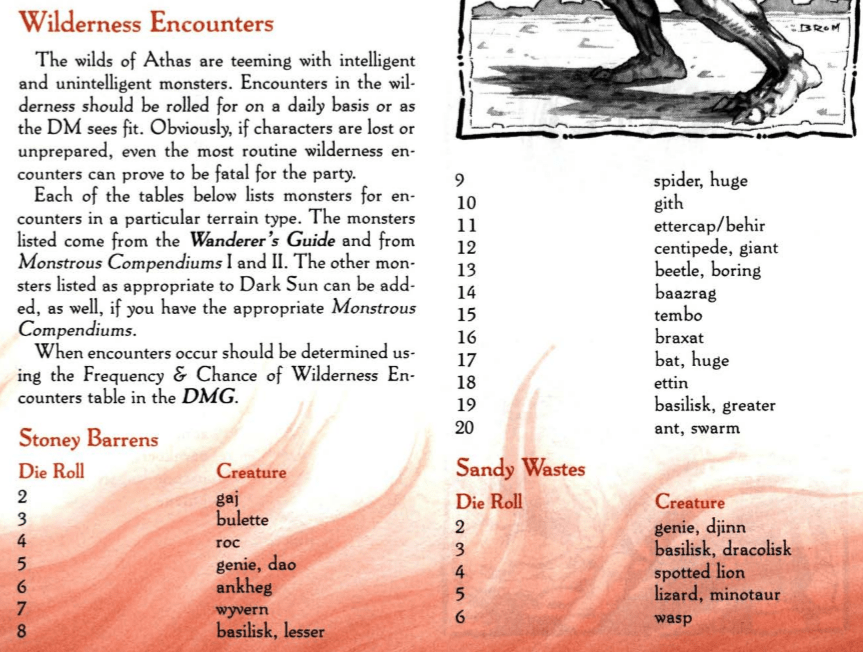

This takes me to another similar topic that comes up often: random encounters. Many DMs love them, while others hate them. Typically we have a table like this one, from the Dark Sun 2E boxed set:

Historically, the point of random encounters, is to represent the unpredictable nature of what might be encountered in a location. This comes from an era when it was perfectly fine to have a planned encounter consisting of a room with nothing more than 4 goblins in an empty room, and the next room might have a basilisk. No story elements or potential energy needed to exist back then. Just rolling dice and controlling a character was enough for this to be fun. Thus, when traversing the wilds or moving between rooms, random encounter tables were perfect.

Today, we expect more from out games. We want a location to have an engrossing story, cool motivations, and fun reveals. And yet, our random encounter tables haven’t changed much. If you look at Wave Echo Cave in Lost Mine of Phandelver, the wandering monsters table is the same historical design:

Why does the design linger, and are there problems with it?

Why Random Encounters Succeed

We are in a corridor in Wave Echo Cave and we roll a d20 and it’s time for a wandering encounter. We get 2 bugbears. Nothing in this situation provides us the spark of fun. We need to bring that ourselves. Otherwise, we have 2 monsters with fairly plain stat blocks and 54 hit points later it’s over with nothing to show for it.

Random encounters, in general, are completely devoid of potential energy. So, why do DMs like them?

Offer a Break: Random encounters can free us from bad design. The adventure might have a series of boring rooms, or a trek across the wilds where we roll to determine if we get lost and make no progress. A fight can take us out of that boredom.

Go Off-Script: Some DMs tend to over-prepare. When everything is too scripted, random encounters provide us with a break from the norm. We get a chance to improvise, which uses different skills and tends to lead in unpredictable directions. We shake up the game.

Collaborative Improvisation: Random encounters can encourage both players and DMs to improvise. The DM can’t possibly think up everything on the fly, so the DM is often introducing information in stages. “You come over the next hill and see a caravan overturned in the middle of the road.” The players might come up with something interesting, which results in the DM adjusting to it. The players split up, so the DM splits the enemy forces, or has a few enemies hiding in the caravan itself. The encounter becomes dynamic because it isn’t fixed.

Why Random Encounters Fail

Falling Flat: Random encounters can just as easily fall flat. We might not be inspired, and because we are improvising, we don’t have notes to save us. Some recent adventures, such as Tomb of Annihilation, provide us with random encounter listings that include a few sentences describing a story seed. These ideas give us a bit of fuel and improve the chances that we can improvise well. Here is an example from that book:

Apes

The characters stumble upon 2d4 apes enjoying some excellent fruit. The apes feel threatened and show signs of defending their food. If the characters immediately back away slowly, the apes do nothing but make threatening displays. Otherwise, they attack.

Challenge Level: It is easy for the encounter we roll up on a chart to be too easy or too hard. Pacing is really important in adventure design and in campaign sessions. When we hit the wrong beats, including the challenge, the session can lose energy or feel frustrating.

Wrong Length: Sometimes we want a quick battle in between two points on a map, but the foes end up taking a while to defeat. Or, we might be hoping to fill a bit of time so we can end at the door to the next place… but the battle finishes quickly and now the players want to enter the dungeon and we end the session in the wrong place.

Wrong Theme: Battles tell stories. Ideally, the story of a random encounter reflects the larger themes in our campaign or adventure. If we have been dealing with a harsh oppressive government in a city, the random encounter is stronger if it reflects that and weaker if it draws us away from that.

Irrelevant to the Campaign: Random encounter tables tend to be lists of creatures that could live in that climate, but seldom tie directly to the campaign’s story or the characters’ goals, exploits, or backstory.

Movies and Novels Fake Their Random Encounters!

When a scriptwriter is crafting a movie, or an author is writing a novel, they aren’t likely to randomly pick what the heroes will face when traveling overland. It might feel random (a forest beast happens upon the heroes), but the design is intentional. Movies carefully and deliberately craft “random” encounters that reflect and heighten the overall narrative, underscore character goals and interests, and highlight the land itself.

Potential Energy and Random Encounters

When designing random encounters, we can utilize potential energy so they are no longer disconnected from our campaign themes, current narrative, or the goals and exploits of the characters. Potential energy can make our random encounters more interesting, more relevant, and turn them into a vital tool in our arsenal.

We can do this in two ways.

Mix of Random Foes and a Story Seed

We can use random encounter tables, but also use a second table or list that contains story seeds for those encounters. By pre-planning some story seeds, we do some of the heavy lifting of improv up front. By keeping them separate from the encounters until we roll dice, we preserve some of the improvisational feel.

The story seeds can reinforce the themes of our adventure, provide clues and references to strengthen our campaign, or relate to the characters and their goals.

Here is an example:

01-10: The monsters have cornered a merchant, who is employed by a faction allied or opposed with the characters. The merchant has an annoying personality and demands to be saved by the characters and taken to the nearest town.

11-20: The monsters have set an ambush, but it has an obvious flaw, allowing the characters to notice something is wrong. The monster’s treasure includes an item from a previous victim who was associated with an ally/foe.

21-30: The creatures are in the process of uncovering a buried treasure. If attacked, they retreat. If treated well, they give a small portion as thanks. During a future random encounter, these creatures will appear and join either the monsters or the characters depending on how they were treated.

31:40: The monsters are here pursuing one of the characters, based on their backstory. Depending on the backstory circumstances, negotiation or other non-combat options may be possible.

41-50: Etc.

Planned Random Encounters

We can take this a step further and actually prepare the “random” encounters ahead of time. We can do this based on the campaign/adventure, and use the best random encounter for the job as needed.

For example, we might prepare encounters such as the following:

- 5 rogues have chased a merchant, who is currently on a log leaning over a precipice. The merchant is incredibly annoying and demands the characters save her. She wears the insignia of an organization with which they are allied. If rescued, she proves to be a thorn in their side until they escort her home.

- 8 Kobolds have set an ambush on either side of a rocky pass. The kobolds have alchemical devices they plan on flinging at the party, but one of them has begun to give off smoke. The characters can see the smoke coming from behind a boulder, and with successful checks hear the kobolds trying to make it stop smoking. The kobolds previously stopped a messenger carrying a missive for one of their foes, and the kobold carrying it might offer it in exchange for her life.

For each encounter, we detail the actual monsters and any other necessary elements (what the terrain looks like, their treasure, what the kobold alchemical devices do, etc.).

As we run our campaign, we pick the encounter that fits the current narrative. Maybe we have had a series of tough fights and we need some levity, so we use the kobold encounter. A few sessions later the characters have befriended an organization, so we use the rogue/merchant encounter to reinforce the relationship with the organization by having the merchant be a member.

We lose some improvisation, but we gain a lot through the robust design.

Regardless of whether we mix random foes and a story seed or go with planned random encounters, the results will let us use lots of potential energy to make those experiences stronger. Our random encounters will become a key part of our campaign narrative and will prove more engaging for our players.

Jungle Treks

When Eric Menge and I designed Jungle Treks, we wanted to do more than provide a few random encounters. We crafted planned encounters that could be used as random encounters, but they were full of story and potential energy that could resonate within an existing campaign.

Take Tavern Trouble, the first encounter. It is inspired by the scene in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, where Indiana Jones has to find an antidote, but it ends up lost in the middle of a crazy fight in a crowded cabaret. In this version, someone the party seeks has run into trouble and a curse has been placed on them. Something happens (I don’t want to spoil the shocking fun) so the cure is hard to find, amidst the chaos of a bar fight. Potential energy abounds so that there are several ways the characters can resolve the situation. The ally the party seeks can simply provide characters information leading to the other encounters in the book, or it can be information relevant to the existing campaign.

In Ambush from Above, a band of grung ambush the party. There are some interesting mechanics the grung use to swing from above down on the characters. More importantly, the grung keep saying a phrase, and they wear strange necklaces… do they have a team mascot? There is the potential for the party to figure out the story behind the mascot can change the course of battle. This can be a simple random encounter, but it can also lead to much more.

In If Looks Could Kill, the party joins a hunting expedition. The personalities of the expedition NPCs create lots of roleplaying potential energy, which the party may or may not resolve by the time the dangerous hunt begins. The results can leave the party with a powerful ally, or with enemies.

To craft these and other encounters, we came up with far more than monsters to randomly encounter. And it wasn’t just a story draped over the battle. We used the principles of potential energy so each “random” encounter engages the characters, surprises the players, reacts to what the characters do, and ties into the story of the larger campaign.

If you enjoyed Jungle Treks, stay tuned! We are currently writing Ice Treks, to accompany the upcoming Icewind Dale adventure from WotC!

Acquisitions Inc?

I originally planned on discussing examples of potential energy found in the Acquisitions Incorporated book. Shawn and I may go back and cover the design of the AI book, so I’m going to hold off on that.

For now, this is the planned end of the series on potential energy. If you would like to see more, let me know what would be helpful. And, I’m curious. How do you feel about random encounters? Let us know in the comments below!

Mastodon

Mastodon BlueSky

BlueSky

Did you ever release the Ice Treks content? Would love to see that if you did

We did not. It pains me, but we saw really poor sales for similar products. And Eric Menge and I were very busy, so we never went beyond the outline stage. It’s a shame. I liked those outlines!